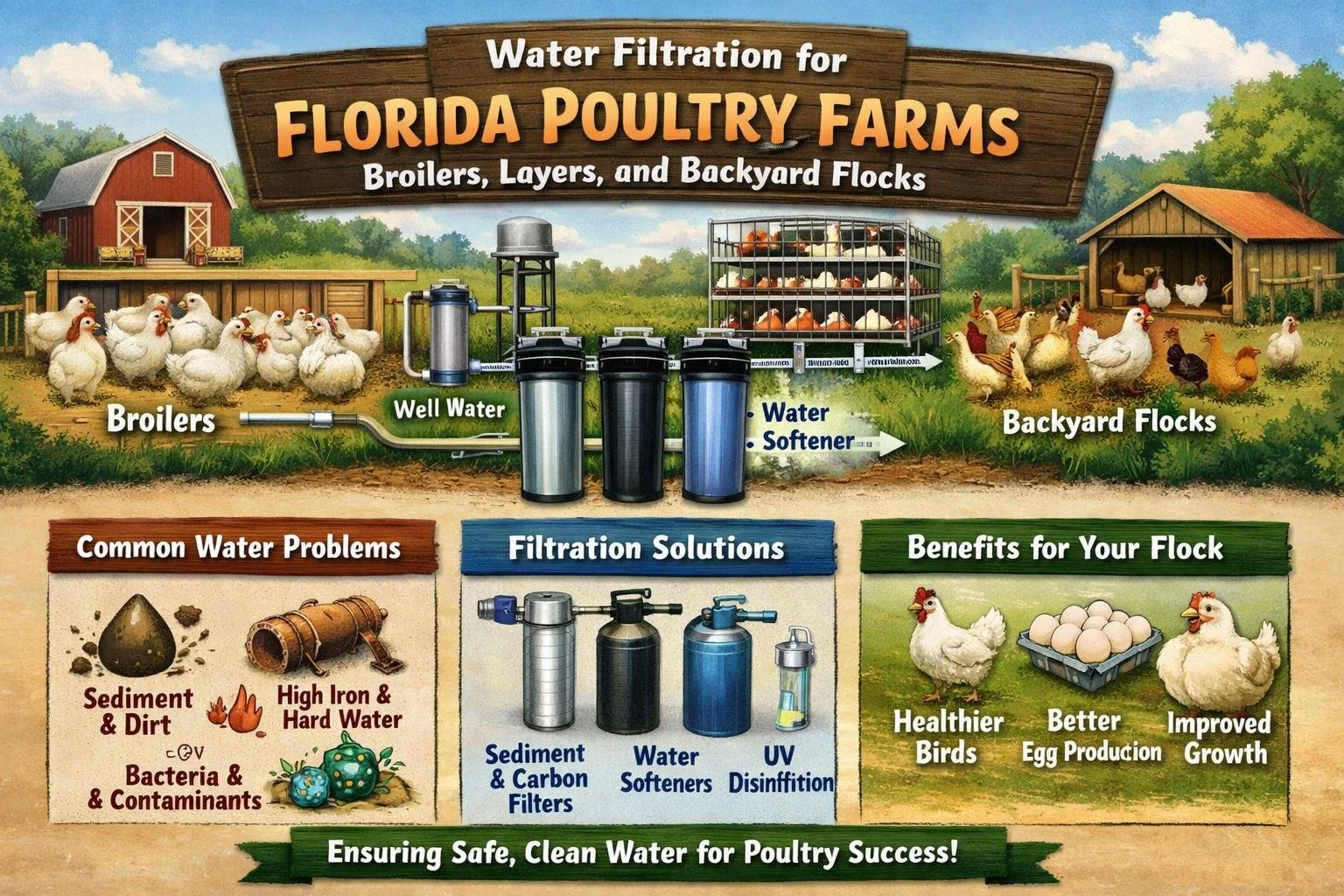

Water Filtration for Florida Poultry Farms: Broilers, Layers, and Backyard Flocks

A Complete Guide to Treating Well Water for Healthy, Productive Birds in the Sunshine State

I remember pulling up to a broiler house outside Bonifay last summer. The grower was convinced something was wrong with his feed—birds were sluggish, conversion ratios were tanking, and mortality had crept up over the past three flocks. Took me about two minutes at the wellhead to figure out what was happening. That sulfur smell hit me before I even got the cap off. His water tested at 4.2 ppm hydrogen sulfide and iron was pushing 3 ppm. The birds weren't sick from feed. They were slowly being poisoned by what should have been their most important nutrient.

Water is everything in poultry production. Your birds consume roughly twice as much water as feed by weight—and during a Florida summer, that ratio can jump to three or four times. Every biological process in a chicken depends on water: nutrient transport, temperature regulation, digestion, waste elimination, even the chemical reactions that build muscle and form eggshells. When that water carries contaminants, every one of those processes suffers.

What makes this particularly challenging for Florida poultry operations—whether you're running contract broiler houses in the Panhandle, managing layers in Central Florida, or just keeping a backyard flock of six hens in Orlando—is the nature of our groundwater. The Floridan Aquifer delivers reliable quantity, but quality is another matter entirely. Iron. Sulfur. Hardness. Bacteria. These aren't occasional problems here; they're baseline conditions that require systematic treatment.

Florida's Poultry Industry: From Commercial Operations to Backyard Flocks

Florida's poultry industry generates substantial economic activity, with broiler production alone valued at $283 million annually and producing over 62 million birds. The state maintains approximately 78.5 million broilers and 11.3 million layers across its commercial operations.

Commercial Broiler Production

The heart of Florida's broiler industry beats in the northern counties, particularly across the Panhandle region. Operations cluster around processing facilities and feed mills in areas like:

DeFuniak Springs and Walton County - Major Perdue Farms operations

Live Oak and Suwannee County - Historical production center

Jacksonville area and Nassau County - Tyson Foods processing complex

Holmes County (Bonifay area) - Dense concentration of contract growers

The integration model dominates Florida broiler production, just as it does nationwide. Integrators like Perdue and Tyson supply birds, feed, vaccines, and technical supervision. Contract growers provide land, labor, housing, utilities, and—critically—water. That last item is where many growers either succeed or struggle.

A typical four-house broiler operation in the Panhandle might place 100,000 to 120,000 birds per flock, running six to seven flocks annually. Each grow-out cycle requires substantial water: drinking water for birds that increases from about 2 gallons per 1,000 birds daily at placement to 80+ gallons per 1,000 birds by market age, plus water for evaporative cooling systems that can demand 8 gallons per minute per house during summer months. A four-house complex might need 25-35 gallons per minute just for drinking water at peak demand, plus another 32 GPM for cool cells.

That's serious volume—and it all has to come from wells drilled into Florida's problematic aquifer.

Egg Production Operations

Layer operations in Florida concentrate in Central Florida, though production data remains partially confidential due to industry structure. Major egg producers have historically operated around Tampa, Lake County, and the I-4 corridor. These operations face the same groundwater challenges as broiler farms but with additional considerations: laying hens are particularly sensitive to water quality variations because shell formation requires precise calcium metabolism, and any disruption to that process shows up immediately in shell quality and egg production rates.

A hen in peak production consumes 270-300 ml of water daily—roughly a pint. Multiply that by operations running hundreds of thousands of birds, and the water demand becomes substantial. More importantly, layers typically remain in production for 12-18 months, meaning any water quality issues have compounding effects over time rather than the 6-8 week grow-out cycles of broilers.

The Backyard Flock Explosion

Perhaps the most dramatic growth in Florida poultry has come from backyard flocks. Thousands of Florida residents now keep small flocks for eggs, pest control, and the simple satisfaction of producing food at home. Most municipalities have developed ordinances permitting residential chicken keeping:

Orange County: Up to 4 hens with permit, UF/IFAS training required

Osceola County: Up to 6 chickens permitted

Jacksonville: Up to 5 hens with permit

Deltona: Up to 10 chickens on half-acre or larger, 5 on smaller lots

St. Cloud: Up to 6 chickens with permit

Escambia County: Up to 8 chickens on lots 0.25 acres or less

These backyard operations might seem insignificant compared to commercial production, but the water quality challenges are identical—and backyard keepers often lack the technical resources available to commercial growers. A family in Winter Garden with four hens has the same need for clean, safe water as a contract grower with 25,000 birds. The scale differs, but the science doesn't.

Why Water Quality Matters: The Bird's Perspective

Here's something that took me years to fully appreciate: a chicken experiences water quality in ways we don't immediately see or understand. They can't tell us the water tastes bad or smells funny. By the time we notice behavioral changes—reduced consumption, lethargy, poor growth—the damage is already accumulating.

The Numbers on Water Consumption

Understanding how much water birds actually consume helps frame why quality matters so intensely:

Broilers consume water at roughly 1.6-2.0 times their feed intake by weight. Modern research from the University of Arkansas Applied Broiler Research Farm shows that daily water consumption per 1,000 birds has increased significantly over the past two decades—from about 140 liters daily in 1991 to 190 liters daily in 2010-2011, reflecting genetic improvements that produce faster-growing, more efficient birds that simply require more water.

At practical application:

Day-old chicks: 1-2 gallons per 1,000 birds daily

3-week-old broilers: 15-20 gallons per 1,000 birds daily

Market-age broilers (6-8 weeks): 50-85 gallons per 1,000 birds daily

Laying hens consume 200-300 ml per bird daily depending on production rate and temperature. A flock in 90% production drinks more than one in 50% production. At peak summer temperatures, consumption can double or triple.

Temperature drives everything. Water consumption increases approximately 7% for every degree Fahrenheit above normal. In Florida, where summer highs regularly exceed 90°F and occasionally push into triple digits, this isn't academic—it's survival. Birds will refuse to drink water that exceeds their body temperature (approximately 106°F), which can happen when water sits in black pipes or storage tanks in direct sunlight.

Water Quality Parameters for Poultry

Commercial poultry operations work with established water quality guidelines. Here's what the science tells us about acceptable levels:

| Parameter | Acceptable | Marginal | Unacceptable |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) | <1,000 ppm | 1,000-3,000 ppm | >3,000 ppm |

| pH | 6.0-6.8 | 6.8-8.0 | <5 or >8 |

| Total Hardness | <110 ppm | 110-250 ppm | >250 ppm |

| Nitrate-Nitrogen | <10 ppm | 10-20 ppm | >20 ppm |

| Nitrite | <0.5 ppm | 0.5-1.0 ppm | >1.0 ppm |

| Sulfate | <50 ppm | 50-250 ppm | >250 ppm |

| Chloride | <50 ppm | 50-150 ppm | >150 ppm |

| Sodium | <50 ppm | 50-150 ppm | >150 ppm |

| Iron | <0.3 ppm | 0.3-1.0 ppm | >1.0 ppm |

| Manganese | <0.05 ppm | 0.05-0.1 ppm | >0.1 ppm |

| Total Bacteria (TPC) | <100 CFU/ml | 100-1,000 CFU/ml | >1,000 CFU/ml |

| Coliform Bacteria | 0 CFU/ml | 1-50 CFU/ml | >50 CFU/ml |

These numbers matter, but the reality on Florida farms often looks quite different. University of Georgia research has shown that iron levels up to 600 ppm and manganese up to 20 ppm may not directly impact bird health in controlled studies—but they absolutely create equipment problems that indirectly devastate performance. Leaky nipples, clogged foggers, failed cooling systems—all traceable to untreated water.

The Cascade of Consequences

Poor water quality creates a cascade of problems that compound over time:

Reduced water intake is the first domino. Birds with sensitive palates (and chickens can taste) will reduce consumption when water tastes or smells off. Sulfur creates that classic rotten-egg odor. High mineral content produces bitter flavors. Even elevated chlorine from over-treatment can back birds off water.

Reduced feed intake follows immediately. The correlation between feed and water consumption runs about 0.98—meaning when water consumption drops, feed consumption drops in almost perfect lockstep. Birds that don't drink don't eat.

Performance collapse comes next. Reduced feed intake directly impacts growth rates in broilers, egg production in layers, and body condition in all birds. A 10% reduction in water intake can translate to equivalent or greater reductions in weight gain or egg numbers.

Health vulnerability develops as birds under nutritional stress become susceptible to disease challenges they might otherwise resist. Respiratory issues, enteric diseases, and general mortality all increase.

Equipment failure accelerates throughout. Iron precipitates clog nipple drinkers, causing some to drip (wet litter problems) and others to stick closed (dehydration in specific areas). Calcium and magnesium scale accumulates in evaporative cooling pads, reducing airflow and cooling efficiency precisely when it's most needed. Biofilms develop in water lines, harboring pathogens and requiring increasingly aggressive cleaning protocols.

Florida's Groundwater: The Challenge We're Dealing With

Every water treatment solution starts with understanding what you're treating. Florida groundwater presents a consistent pattern of challenges that vary somewhat by region but share common characteristics.

Iron: The Universal Florida Problem

Iron contamination ranks as the single most common water quality issue across Florida. Concentrations typically range from 0.5 to 5+ ppm, with some wells testing considerably higher. The iron exists in groundwater as ferrous iron (Fe²⁺)—clear and dissolved—but oxidizes to ferric iron (Fe³⁺) when exposed to air, producing the characteristic rust-colored water that stains everything it touches.

For poultry operations, iron creates multiple problems:

Nipple drinker failure: Iron precipitates accumulate on pins and seals, causing drinkers to stick or drip

Bacterial growth: Iron bacteria (Gallionella, Leptothrix) thrive in iron-rich water, producing slimy deposits and contributing to biofilm formation

Medication and vaccine interference: Iron can bind with certain water-soluble medications and vaccines, reducing their effectiveness

Cooling system damage: Iron deposits accumulate in cool cell pads, reducing evaporative efficiency

Taste effects: While research suggests birds tolerate moderate iron levels health-wise, many growers report reduced consumption with high-iron water

Hydrogen Sulfide: Florida's Signature Smell

That sulfur smell is practically synonymous with Florida well water. Hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) forms when sulfate-reducing bacteria metabolize sulfate compounds in low-oxygen conditions within the aquifer. Concentrations commonly range from 1-5 ppm, though some wells test much higher.

Hydrogen sulfide is directly toxic to poultry at elevated levels. Even at sub-lethal concentrations, it:

Reduces water palatability (birds avoid the smell just like we do)

Corrodes metal components throughout the water system

Interferes with chlorination (H₂S consumes chlorine before it can disinfect)

Combines with iron to form black iron sulfide deposits

The sulfur smell is actually a warning sign—by the time you can smell it (typically around 0.5 ppm), concentrations may be high enough to impact bird performance and equipment longevity.

Hardness and Scale: The Slow Accumulation

Florida groundwater hardness typically ranges from 15-30 grains per gallon (250-500 ppm as calcium carbonate), though some regions test considerably higher. Hardness itself doesn't harm birds directly—chickens tolerate hard water reasonably well. The problems emerge over time:

Scale accumulation develops gradually in water lines, particularly in areas where water sits or flows slowly. Pressure regulators, water line ends, and medicator systems all become scale traps. Once scale establishes, it provides protected habitat for bacteria and makes disinfection increasingly difficult.

Medication and vaccine interference occurs when hard water minerals interact with certain products. Tetracyclines, for example, can chelate with calcium and magnesium, reducing their effectiveness. Hard water also impacts vaccine stability during administration.

Evaporative cooling system degradation represents perhaps the most visible hardness impact. Cool cell pads accumulate scale deposits that progressively reduce airflow and evaporative efficiency. In Florida's summers, that degradation directly translates to heat stress risk.

Bacterial Contamination: The Hidden Threat

Private wells don't receive the chlorination that municipal water systems provide. Surface water infiltration—particularly during heavy rains—can introduce bacterial contamination ranging from general heterotrophic bacteria to specific pathogens like E. coli, Salmonella, and Campylobacter.

Bacterial presence in source water becomes dramatically amplified within poultry watering systems. The combination of warmth, nutrients from supplements and medications, and biofilm protection creates ideal conditions for bacterial proliferation. A water source testing at 100 CFU/ml at the wellhead can easily reach 10,000+ CFU/ml by the time it exits nipple drinkers at the far end of a 500-foot house.

This is why the antibiotic-free (NAE) and "no antibiotics ever" production programs have focused such intense attention on water quality. Without antibiotics as a safety net, water-borne pathogens present far greater risk than they did under conventional production programs.

The Florida Heat Factor: When Water Becomes Critical

Florida's subtropical climate adds another layer of complexity to poultry water management. Heat stress begins affecting bird performance when ambient temperatures exceed 80°F—a threshold we blow past for roughly half the year. At temperatures above 85°F, heat stress becomes severe. When thermometers hit the mid-90s with high humidity, we're in mortality event territory.

How Heat Changes Water Requirements

Birds respond to heat stress by increasing water consumption dramatically. They pant to drive evaporative cooling through their respiratory tract, losing significant water in the process. Practical numbers:

At 68°F: Normal water consumption (baseline)

At 86°F: Water consumption increases 50-75%

At 95°F: Water consumption may double or triple baseline

Above 100°F: Water consumption can quadruple or more

This creates two overlapping demands: birds need more water precisely when that water faces greater bacterial growth risk (warmth accelerates proliferation) and greater equipment stress (scale precipitation increases at higher temperatures).

Water Temperature Matters

Here's something many growers overlook: birds will refuse water that's too warm. Research shows chickens will suffer extreme thirst rather than drink water that's even a few degrees above their body temperature (approximately 106°F). Water sitting in black polyethylene lines exposed to Florida sun can easily exceed 120°F—hot enough that birds won't touch it.

Cool water provides dual benefits: birds drink more of it, and the water itself absorbs body heat during consumption, providing additional cooling effect. Water at 50-60°F can significantly improve performance during heat events compared to water at 85°F.

This creates design considerations for Florida operations:

Burying supply lines to buffer temperature

Painting storage tanks white or shading them

Flushing lines regularly during peak heat to remove warm water

Sizing systems to maintain flow (moving water stays cooler than stagnant water)

Evaporative Cooling Demands

Most commercial Florida poultry houses rely on tunnel ventilation with evaporative cooling—those characteristic cool cell pads at one end of the house. These systems consume enormous water volumes: 8-10 gallons per minute per house is typical, with larger houses requiring more.

That water all comes from the same well supplying drinking water, facing the same quality challenges. Iron deposits and scale accumulation gradually destroy cool cell efficiency, sometimes over just two or three seasons without proper water treatment. Replacement pads cost thousands of dollars, but the real expense is the lost cooling capacity during critical summer weeks—capacity that translates directly to bird mortality and performance losses.

Water Treatment Solutions for Poultry Operations

Effective water treatment for Florida poultry farms typically requires addressing multiple contaminants simultaneously. A single-technology solution rarely suffices. The good news: treatment technologies are well-established, and we've developed effective protocols specifically for agricultural applications.

Stage 1: Sediment Filtration

Before any other treatment, water needs physical filtration to remove particulates—sand, silt, and organic debris that would otherwise overwhelm downstream treatment systems.

Spin-down separators provide effective first-stage removal of larger particles (50+ microns). These centrifugal separators require no filter media replacement—just periodic flushing to clear accumulated sediment from the collection chamber. For a 4-house broiler operation, a 2" spin-down rated for 50-100 GPM provides adequate capacity.

Sediment filter cartridges catch finer particles that pass spin-down separators. Standard 20" or 4.5" x 20" "Big Blue" cartridges in 5-25 micron ratings are typical for poultry applications. Pleated cartridges offer longer service life than spun polypropylene for the same micron rating. Plan to replace cartridges every 2-4 weeks during heavy use, more frequently if source water carries significant sediment.

Multi-media filters (sand/anthracite) provide higher-capacity filtration for larger operations. These backwashing filters can handle significant sediment loads and regenerate automatically. A 13" x 54" multi-media filter handles 10-15 GPM continuous flow—sufficient for a small to medium operation.

Stage 2: Iron and Sulfur Removal

This is the critical treatment stage for most Florida poultry operations. Several technologies effectively address iron and sulfur, each with different characteristics:

Air Injection Oxidation (AIO) Systems

These systems oxidize iron and hydrogen sulfide by injecting air into the water stream, then filter the oxidized precipitates. Modern AIO systems like the SpringWell WS series combine aeration and filtration in a single tank using a specialized air-injection head.

Advantages:

No chemicals required—chemical-free operation

Handles moderate iron (up to 7-8 ppm) and H₂S (up to 3-5 ppm)

Automatic backwashing regeneration

Low ongoing maintenance costs

Limitations:

Requires adequate water pressure (30+ PSI)

May struggle with very high iron or sulfur levels

Backwash cycle uses 40-60 gallons—needs adequate supply

For a typical Florida poultry operation with moderate iron and sulfur, an AIO system in the 1.5-2.5 cubic foot size range handles 10-20 GPM continuous flow, sufficient for most 4-6 house operations when combined with adequate storage.

Chemical Oxidation Systems

For severe iron and sulfur contamination (iron above 8 ppm, H₂S above 5 ppm), chemical oxidation provides more aggressive treatment:

Chlorine injection oxidizes both iron and H₂S effectively. A metering pump injects sodium hypochlorite solution (household bleach or calcium hypochlorite) upstream of a contact tank, allowing oxidation time before filtration removes precipitates.

Hydrogen peroxide injection provides powerful oxidation without adding chlorine byproducts. Particularly effective against hydrogen sulfide—peroxide directly converts H₂S to elemental sulfur.

Ozone systems generate ozone on-site for injection into water. Ozone is the most powerful oxidizer commonly used in water treatment, highly effective against iron, sulfur, and bacterial contamination. Higher capital cost but excellent performance.

After chemical oxidation, a carbon filter or specialized iron filter removes oxidized precipitates. The combination handles virtually any iron and sulfur contamination level found in Florida groundwater.

Stage 3: Carbon Filtration

Activated carbon provides multiple functions in poultry water treatment:

Chlorine/chloramine removal: Essential if using chlorinated municipal water or if upstream chlorination is part of the treatment train

Organic compound removal: Reduces taste and odor compounds that affect palatability

Chemical residue reduction: Provides buffer against trace contaminants

For operations using municipal water, carbon filtration is essential—chlorine at municipal treatment levels (1-4 ppm) will harm birds and interfere with medications and vaccines. For well water systems, carbon provides insurance against organic contamination and removes any chlorine residuals from oxidation treatment.

Carbon filter sizing depends on flow rate and desired contact time. A 1.5 cubic foot carbon filter provides adequate capacity for 10-15 GPM for most poultry applications.

Stage 4: Disinfection

Controlling bacterial contamination requires ongoing disinfection—not just at the source, but maintaining residual protection throughout the distribution system.

Chlorination remains the industry standard for poultry water disinfection. The goal is maintaining 3-5 ppm free chlorine at the drinker farthest from the injection point. This requires:

Proportioner or metering pump to inject chlorine solution

pH control (chlorine effectiveness drops dramatically above pH 7)

Regular testing to verify residual levels

Critical point: chlorine effectiveness depends entirely on pH. At pH 7.0, chlorine forms hypochlorous acid (HOCl), which kills bacteria 80 times more effectively than the hypochlorite ion (OCl⁻) that dominates at pH 8.0+. If your source water runs alkaline (common in Florida), acidification before chlorination dramatically improves disinfection performance.

Chlorine dioxide offers advantages over standard chlorination:

Effective over wider pH range (4-10)

Better biofilm penetration

No chlorinated byproducts

Doesn't affect water taste at treatment levels

Removes sulfur odors

Chlorine dioxide systems generate ClO₂ on-site by mixing precursor chemicals. More complex than simple chlorination but increasingly popular in NAE production programs.

UV sterilization provides chemical-free disinfection through ultraviolet light exposure. UV systems sized at 40-100 mJ/cm² dose effectively inactivate bacteria, viruses, and protozoa.

UV advantages: no chemicals, no taste effects, no residuals to manage UV limitations: no residual protection downstream, requires clear water (must follow iron/sediment removal), lamp replacement every 12-18 months

Many commercial operations use UV as primary disinfection with low-level chlorination for residual protection through the distribution system.

Addressing Hardness and Scale

Water softening for poultry operations requires careful consideration. Traditional ion-exchange softeners remove calcium and magnesium but replace them with sodium—and poultry are sensitive to elevated sodium levels. Options include:

Selective softening: Treating only cooling system supply water while leaving drinking water unsoftened. Birds tolerate moderate hardness; cooling systems don't.

Polyphosphate treatment: Chemical injection that keeps hardness minerals in solution rather than removing them. Prevents scale formation without adding sodium.

Template Assisted Crystallization (TAC): Media that converts hardness minerals into microscopic crystals that don't form scale. No salt required, no sodium added.

For operations with severe hardness (above 25 GPG), reverse osmosis provides complete mineral removal—but at significant cost and with substantial wastewater generation. RO is rarely justified for poultry drinking water but may be appropriate for specific applications like hatchery water supply.

Treatment System Design by Operation Type

Water treatment needs scale with operation size and type. Here's how to approach system design for different Florida poultry operations:

Commercial Broiler Operations (4-8 Houses)

A typical Panhandle broiler operation with 4-8 houses requires a treatment system capable of handling peak drinking water demand plus cooling system demand. Design parameters:

Peak flow requirement: 30-50 GPM drinking water + 30-80 GPM cooling (4-8 houses)

Daily volume: 5,000-15,000 gallons drinking water at peak bird ages, plus cooling

Treatment goals: Iron below 0.3 ppm, sulfur below 0.5 ppm, bacteria-free supply

Recommended system components:

| Component | Specification | Estimated Cost |

|---|---|---|

| Spin-Down Separator | 2" centrifugal, 100 GPM rated | $300-600 |

| Sediment Filter Housing | Big Blue 20" dual housing, 5-micron cartridges | $200-400 |

| Iron/Sulfur System | 2.5 cu ft AIO or chemical oxidation + filter | $3,500-8,000 |

| Carbon Filter | 2.0 cu ft backwashing carbon | $1,500-2,500 |

| UV System | 50-100 GPM commercial UV | $2,000-4,000 |

| Chlorination System | Proportioner + tank for residual disinfection | $500-1,200 |

| Storage Tank | 2,500-5,000 gallon treated water storage | $2,000-5,000 |

| Pressure System | Booster pump + pressure tank if needed | $1,000-2,500 |

| TOTAL SYSTEM | Complete treatment train | $11,000-24,000 |

Annual operating costs for a commercial broiler treatment system typically run $2,000-5,000:

Sediment filter cartridges: $200-500

Carbon replacement (every 3-5 years, annualized): $300-600

UV lamp replacement: $200-400

Chlorine/chemicals: $500-1,500

Water testing: $400-800

Professional maintenance: $400-1,200

Layer Operations

Layer operations require similar treatment capacity but with additional considerations for the extended production cycle. Water quality consistency matters more when birds remain in production for 12-18 months versus 6-8 week broiler cycles.

System design parallels broiler operations, with emphasis on:

Stable pH maintenance (critical for eggshell quality)

Consistent mineral content (calcium/phosphorus balance affects shell formation)

Excellent bacterial control (layers more susceptible to chronic infections affecting production)

Calcium in water actually benefits layers somewhat—unlike other livestock that may require softening, moderate hardness supplies dietary calcium that supports shell production.

Backyard Flock Operations (4-12 Birds)

Small-scale chicken keepers face the same water quality challenges on a smaller scale. Treatment systems scale down accordingly:

Minimal approach (tight budget):

Gravity-fed carbon filter for chlorine removal (municipal water): $40-100

Regular water testing: $50-100/year

Clean waterers daily

Basic treatment (well water):

Small whole-house iron/sulfur filter: $800-1,500

Point-of-use sediment filter: $50-100

Annual water testing: $100-200

Comprehensive backyard system:

Complete whole-house treatment (iron, sulfur, sediment, carbon): $2,000-4,000

Small UV system: $300-600

Water testing program: $200-400/year

| Approach | Components | Initial Cost | Annual Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Municipal Water (Minimal) | Carbon filter pitcher + testing | $40-100 | $50-150 |

| Well Water (Basic) | Small iron filter + sediment | $800-1,500 | $150-300 |

| Well Water (Complete) | Full treatment system + UV | $2,000-4,500 | $250-500 |

Hatchery Operations

Hatcheries require the most stringent water quality standards. Eggs and newly hatched chicks are extraordinarily vulnerable to contamination, and any pathogen introduction at this stage cascades through the entire production system.

Hatchery water treatment typically includes:

Fine sediment filtration (5 micron or finer)

Complete iron and sulfur removal

High-capacity carbon filtration

High-dose UV sterilization (100+ mJ/cm²)

Temperature control (precise temperature management for incubators)

Optional: reverse osmosis for maximum purity in critical applications

System costs for hatchery water treatment typically run $15,000-40,000 depending on capacity and purity requirements.

The Economics of Water Treatment: ROI Analysis

Water treatment represents a significant investment. Understanding the return on that investment helps justify the expense and guides appropriate system selection.

Cost of Poor Water Quality

The true cost of untreated or poorly treated water includes both direct and indirect losses:

Direct mortality events: A single heat stress event where compromised cooling systems fail can kill thousands of birds in hours. A 100,000-bird complex losing 5% to heat stress represents $15,000-25,000 in direct bird value—not counting lost production time, disposal costs, and contract penalties.

Chronic performance depression: Subtle water quality issues that don't cause acute mortality still impact the bottom line through:

Reduced feed conversion (5-10% worse FCR = significant cost per flock)

Decreased growth rates (lighter birds at market age)

Increased condemnations at processing

Higher medication costs for preventable health issues

Equipment degradation: Scale-damaged cool cell pads cost $3,000-8,000 to replace per house. Nipple drinker replacement runs $5,000-10,000 per house for complete refit. Premature failure of pressure regulators, medicators, and other components adds up quickly.

Veterinary and medication costs: Water-borne health challenges require treatment—antibiotics (where permitted), probiotics, electrolytes, and veterinary consultation all add cost.

Return on Investment Calculation

For a 4-house broiler operation investing $15,000 in water treatment:

| Benefit Category | Annual Value | Assumptions |

|---|---|---|

| Reduced Mortality | $4,000-8,000 | 1-2% mortality reduction, 6 flocks/year |

| Improved FCR | $3,000-6,000 | 2-3 point FCR improvement |

| Equipment Longevity | $2,000-4,000 | Extended cool cell, drinker life |

| Reduced Health Costs | $1,000-3,000 | Lower medication, vet expenses |

| Total Annual Benefit | $10,000-21,000 | |

| Less: Operating Costs | ($3,000-5,000) | Filters, chemicals, maintenance |

| Net Annual Benefit | $7,000-16,000 |

At these returns, a $15,000 treatment system pays for itself in 1-2 years, with ongoing net benefits thereafter. More importantly, water treatment provides insurance against catastrophic loss events that could otherwise devastate an entire operation.

For backyard operations, the math works differently but still favors treatment. A single veterinary visit for sick birds can cost $100-300. Losing birds to preventable water-quality issues wastes months of feeding and care investment. A $2,000 treatment system protecting a $500 investment in birds plus years of egg production makes practical sense.

Water Line Management: Beyond Treatment

Even perfectly treated water degrades as it moves through distribution systems. Water line management is as important as source water treatment.

The Biofilm Problem

Biofilm is the invisible enemy in poultry watering systems. This slimy matrix of bacteria, organic material, and mineral deposits accumulates on interior pipe surfaces, providing protected habitat for pathogens including Salmonella, E. coli, and Campylobacter.

Biofilm develops in layers:

Organic conditioning film forms on pipe surfaces within hours of water contact

Bacteria attach to conditioning film and begin reproducing

Bacteria produce extracellular polymeric substances (EPS)—the "slime"

EPS matrix protects bacteria from disinfectants

Mature biofilm continuously releases bacteria into water flow

Even aggressive chlorination struggles to penetrate established biofilm. The protective matrix allows bacteria to survive chlorine levels that would kill them in open water. This is why growers sometimes find high bacterial counts at drinkers despite maintaining proper chlorine residuals.

Between-Flock Cleaning Protocol

Thorough water line cleaning between flocks is essential. A typical protocol:

Step 1: Drain and flush

Remove all water from lines

High-pressure flush to remove loose debris

Allow lines to drain completely

Step 2: Cleaning solution

Fill lines with concentrated cleaning solution

Options include:

Hydrogen peroxide (35-50% concentration): 3-4 oz per gallon of line capacity

Chlorine bleach: 1 cup per gallon (creates 10,000+ ppm solution)

Commercial cleaners (Proxy-Clean, KleanGrow, etc.): per label directions

Allow minimum 24-hour contact time

Some protocols call for periodic agitation (raising/lowering lines)

Step 3: Flush thoroughly

Flush all cleaning solution from system

Test flush water for chemical residual

Continue flushing until residual reaches safe levels

Step 4: Verify

Test water at far end of lines for bacterial counts

Confirm chlorine levels are appropriate before bird placement

During-Flock Water Management

With birds in the house, water management focuses on maintaining quality rather than aggressive cleaning:

Daily tasks:

Check pressure and flow at multiple points

Verify chlorine residual (target 3-5 ppm at far end)

Monitor water meter readings (sudden changes indicate problems)

Trigger drinkers to test for proper function

Weekly tasks:

Flush water lines (allow birds to drink lines dry, then flush)

Check filters, replace as needed

Test pH and chlorine levels

Inspect for leaks and drips

After medications or supplements:

Flush lines thoroughly to remove residues

Medications can leave carrier residues that promote bacterial growth

Vaccines can interact with disinfectants—follow label directions

Line Acidification

Many successful Florida operations maintain mildly acidic water (pH 5.5-6.5) throughout production. Benefits include:

Enhanced chlorine effectiveness

Reduced scale formation

Mild bacterial suppression

Improved palatability for some birds

Acidification options include citric acid, phosphoric acid, and various organic acid blends. Organic acids like propionic and formic acid provide additional antimicrobial benefits beyond pH reduction.

Caution: Never mix chlorine and acid in the same stock solution—this generates toxic chlorine gas. Inject separately with adequate distance between injection points.

Water Testing: What to Test and When

Effective water management requires regular testing to identify problems early and verify treatment system performance.

Baseline Testing

Before installing any treatment system—or when taking over a new operation—establish baseline water quality through comprehensive testing:

Full panel (annually): $150-300

pH

Total dissolved solids

Hardness

Iron

Manganese

Sulfate

Nitrate/nitrite

Chloride

Sodium

Calcium

Magnesium

Total coliform bacteria

E. coli

Optional additions (if indicated):

Heavy metals panel (lead, arsenic, copper)

Hydrogen sulfide (difficult to test accurately—often estimated by odor or proxy measurements)

Pesticide screen (if agricultural contamination suspected)

Routine Testing

| Test | Frequency | Method | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorine residual | Daily | Pool test kit or strips | $0.10-0.25/test |

| pH | Weekly | Test strips or meter | $0.10-0.50/test |

| Bacteria (TPC) | Monthly | Lab test or Petrifilm | $15-50/test |

| Iron/hardness | Quarterly | Test kit or lab | $10-30/test |

| Full panel | Annually | Laboratory analysis | $150-300/test |

Testing Locations

Where you sample matters as much as what you test:

At the well/source: Establishes raw water quality

After treatment: Verifies treatment system performance

At the first house: Confirms treated water reaches birds

At the far end of lines: Identifies degradation through distribution

At drinker nipples: Shows actual water quality birds receive

Significant variation between these points indicates distribution system problems requiring attention.

Florida-Specific Considerations

Hurricane and Storm Preparedness

Florida's hurricane season (June through November) brings additional water quality challenges:

Before storms:

Fill treated water storage to maximum capacity

Ensure generator backup for treatment systems and well pumps

Stock extra filter cartridges and treatment chemicals

Document current water test results for post-storm comparison

After storms:

Test water before resuming use—surface contamination can enter wells during flooding

Inspect wellheads for damage or debris intrusion

Shock chlorinate if contamination suspected

Flush entire system before bird placement

Seasonal Variation

Florida groundwater quality varies somewhat seasonally:

Rainy season (June-September):

Increased surface water infiltration risk

Higher bacterial counts possible

More sediment in shallow wells

Test more frequently during heavy rain periods

Dry season (November-May):

More stable water quality

Higher mineral concentrations possible as water table drops

May need to increase filtration capacity if sediment increases

Regional Differences

Water quality varies across Florida regions:

Panhandle: Generally moderate iron and sulfur, variable hardness. Many wells tap into younger, sandier formations with better baseline quality than Central Florida.

North Central Florida: Variable quality depending on specific geology. Karst terrain creates rapid changes in water quality; wells near sinkholes require extra vigilance.

Central Florida: Often higher hardness and sulfur. Orange-producing regions may have residual agricultural chemicals requiring carbon filtration.

South Florida: Higher TDS and sodium levels as aquifer approaches salt water interfaces. Monitor for saltwater intrusion, particularly after extended droughts.

Working With Water Wizards: Our Approach to Poultry Water Treatment

At Water Wizards, we've developed our poultry water treatment expertise through years of working with Florida farms across the spectrum—from massive broiler complexes to backyard coops. Our approach emphasizes:

Comprehensive Assessment

We start by understanding your operation: bird type, flock size, housing configuration, current challenges, and goals. Then we conduct thorough water testing at multiple points to characterize your specific water quality profile.

Customized System Design

Cookie-cutter solutions don't work for water treatment. We design systems matched to your actual water chemistry, flow requirements, and operational needs. A 6-house broiler operation in Bonifay needs different treatment than a 50-hen layer operation in Ocala, even if both have "iron and sulfur problems."

Professional Installation

Proper installation determines system performance. Our team handles complete installation including:

Plumbing modifications

Electrical connections

System programming and calibration

Initial testing and verification

Training and Support

The best treatment system in the world fails without proper operation. We train your team on:

Daily monitoring procedures

Filter change protocols

Chemical handling safety

Troubleshooting common issues

When to call for service

Ongoing Maintenance Programs

Optional maintenance agreements ensure your system continues performing:

Scheduled filter changes

Annual system inspection

Media replacement when needed

Priority service response

Updated water testing and system optimization

Service Area

We serve poultry operations throughout Florida, with particular concentration in:

Panhandle region: Walton, Holmes, Jackson, Washington, Okaloosa counties

North Florida: Suwannee, Columbia, Alachua, Marion counties

Central Florida: Lake, Orange, Polk, Osceola counties

Tampa Bay region: Hillsborough, Pinellas, Manatee counties

For operations outside these core areas, we provide consultation, system design, and can coordinate with local installers for implementation.

Frequently Asked Questions

What's the most important water treatment for a poultry operation?

Iron and sulfur removal typically ranks as the highest priority for Florida operations because these contaminants cause both direct bird health impacts and equipment damage. However, the "most important" treatment depends on your specific water chemistry—a well with low iron but high bacteria requires different prioritization than one with severe iron but sterile water. Start with comprehensive testing to identify your specific challenges.

How often should I replace filter cartridges?

Sediment pre-filters typically need replacement every 2-4 weeks in commercial operations, more frequently during periods of high sediment load. Carbon filters last 3-6 months for cartridges, 3-5 years for backwashing tank systems. UV lamps should be replaced annually regardless of appearance—output degrades before visible failure occurs. Your specific replacement schedule depends on water quality and system sizing.

Can I use municipal water for my chickens?

Yes, but municipal water requires dechlorination before use. Chlorine at municipal treatment levels (typically 1-4 ppm) can harm birds and interferes with medications and vaccines. A simple carbon filter removes chlorine effectively. If your municipal water is chloraminated (uses chloramines rather than free chlorine), ensure your carbon filter is rated for chloramine removal—standard carbon is less effective against chloramines.

What pH is best for poultry water?

Research indicates birds prefer and perform best with slightly acidic water in the 6.0-6.8 pH range. This pH range also maximizes chlorine disinfection effectiveness. Water with pH above 8.0 may reduce consumption and dramatically reduces chlorine effectiveness. If your source water runs alkaline (common in Florida), acidification improves both palatability and disinfection performance.

How do I know if water quality is causing my flock problems?

Warning signs of water-quality issues include: reduced water consumption, wet litter under drinkers (indicating leaking/dripping nipples), visible staining in waterers or sinks, sulfur smell, poor feed conversion without other explanation, increased mortality or condemnations, and declining egg production or shell quality in layers. When you notice these issues, test water quality and inspect treatment systems before assuming feed or disease problems.

Is reverse osmosis necessary for poultry water?

For most poultry operations, RO is overkill. Properly designed conventional treatment (iron/sulfur removal, carbon, UV) provides adequate water quality at far lower cost and without the wastewater RO systems generate. RO may be appropriate for specific applications like hatchery supply water where maximum purity is required, or in areas with extreme mineral contamination or saltwater intrusion.

How much does professional water treatment cost compared to doing it myself?

DIY installation can save 30-50% on initial costs if you have plumbing skills and water treatment knowledge. However, improperly sized or installed systems underperform, potentially costing more in the long run through inadequate treatment, premature failure, or both. Professional installation ensures correct sizing, proper configuration, and warranty coverage. For commercial operations where water quality directly impacts livelihood, professional installation usually proves cost-effective.

Water Wizards Filtration provides comprehensive water treatment solutions for Florida poultry operations of all sizes. From commercial broiler complexes to backyard flocks, we design and install treatment systems that deliver the clean, safe water your birds need to thrive.

Contact us for a free water quality assessment and treatment system consultation.